No fancy introduction – no attempted clever word-play. This is another list – and few are bigger than this one in terms of their musical importance and influence.

Between 1963 and 1970, The Beatles released eleven studio albums in the UK. They are listed below in ascending order of merit, with some kind of commentary justifying their relative position.

Naturally – I do not know what I’m talking about and claim no greater insight than my opinion. Maybe you’ll agree with some of it – most likely, you won’t – but maybe you’ll consider the views a bit before leaving in disgust.

Enjoy….

Yellow Submarine (January 1969)

To start (almost) at the end…

Throughout their career, The Beatles were often at, if not the, cutting edge of popular culture, the weren’t just a part of the zeitgeist, they were the zeitgeist.

This album finds them, at best, chasing their own psychedelic tail and at worst, simply cashing in on the grooviness.

‘All You Need is Love’ stands out alongside the title track in terms of the songs that have endured – but it’s impossible to take ‘Yellow Submarine’ out of its time of creation and see if it stands on pure merit. It doesn’t. Even weirder is the title track – originally appearing on ‘Revolver’ three years earlier. No-one would have thought for an instant that a throwaway ditty of sub-aqua existence could have taken on such a life – but then again, LSD wasn’t quite so popular in 1966

So -released in January 1969 – at the tail end of psychedelia’s sway over certain hearts, minds and central nervous systems, it arrived too late. Whether it needed to arrive at all is debatable.

It’s certainly better than ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ which truly marks the nadir of the Fabs’ career – but as this was released as a double EP in 1967 and not as an album (although purists will argue that an 8-Track option was available) until 1976 – we’re going to discount it from the list. And rightly so.

The Beatles didn’t voice their own characters in the film. This lack of engagement seems to reflect how time and the critical gaze views the album. The late sixties were not devoid of those touched by genius, but it was also populated by chancers who thought that lots of primary colours, swirly animations and Afghan coats were enough to claim validity. This falls into the latter category.

With The Beatles (November 1963)

The ‘difficult’ second album didn’t seem so hard. Released less than 7 months after ‘Please Please Me’, the sophomore LP came quickly on the heels of the debut – but with significantly less quality.

The road to a second album must have been a busy one. One can only imagine the pressures being put on the band to capitalise on their success and perhaps this shows as from the 14 tracks, 8 are original (7 to Lennon & McCartney, 1 ( ‘Don’t Bother Me’) to Harrison. Fortunately for the band and their management, the choice of covers showed their range. ‘Money’ and ‘Roll Over Beethoven’ provide the rock edge with ‘Till then there was you’ showing their softer side. However – in the unoriginality lies the flaw. This is a 50% cover album and has the whiff of a boy band being shamelessly fattened-up and rushed to market.

From those 8 original numbers, ‘All My Loving’ is the standout – perhaps alongside ‘ I wanna Be Your Man’ – and actually these are not great. The knockabout jolliness of the former and the raunchier punch of the latter being little more than pastiches of the covers already mentioned.

Trading on more than songwriting talent was nothing new in 1963 and maybe one should judge this album less harshly. However, with a little more time and nurture, who knows what might have been?

Beatles For Sale (December 1964)

A scan down the track listing of ‘Beatles for Sale’ throws up ‘Eight Days a Week’ as the household name and poses a few questions for the casual fan.

The accepted practice of padding out the tracks with cover versions continues in the form of tunes from amongst others, Chuck Berry, Carl Perkins and Buddy Holly. 8 of the 14 tracks are originals and ‘Eight Days a Week’ aside, the others seem to show their influences rather too much with elements of skiffle and tell-tale Holly-esque guitar parts combining to create tunes that don’t really transcend the level of pastiche.

What does set them apart though is the manner in which these versions are presented. The vocals maintain a rawness as well as their emerging beauty and the overall musical quality is clear to see. If anyone had any doubt at the time, that The Beatles were going be a flash in the pan, there’s enough here to point to longevity.

Considering the ridiculous touring schedule that the band were subjecting themselves to at the time, it’s actually impressive that eight original tracks got written at all. These may not be the best the ever made but being made they were,

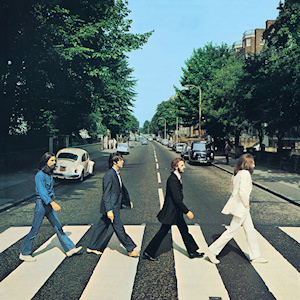

Abbey Road (September 1969)

Although this album contains so much iconography and seems to have a great deal of public affection, by the time of its release the writing was on the wall and The Beatles were on the slide.

The opener ‘Come Together’ has taken on an FM radio favourite life of it’s own – and does feature some of Ringo’s best work. Track 2, ‘Something’ is a tender, delicate love song – but it’s better known as a George Harrison track as is ‘Here Comes The Sun’ a tune that can not help but lift the spirits.

‘Abbey Road’ has probably the second most famous Beatles LP cover and the enduring ‘Paul is dead’ myth has given it an extra dimension. It is a great piece of album presentation – but when an album cover is better known than what it is covering, this raises questions.

The problem with Abbey Road is that there is so much filler amongst the gems. May 7, 1969 had seen the Altamont festival’s descent into brutish murder and the end of the sixties had been announced. No one seemed to have told The Beatles – and the non-consequential whimsy of ‘Mean Mr Mustard’, ‘Polythene Pam’, ‘Octopus’s Garden’ and the unspeakably awful ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’ seem rather ‘last year’ (if not a whole era away) from The Stones’ ‘Let It Bleed’ which followed in December. Compare always anything on ‘Abbey Road’ to ‘Gimme Shelter’ and the former seems somewhat…flimsy.

The times were certainly a-changin’ – things were on the move. Having driven the bus for so long – The Beatles had now seem to have missed it entirely.

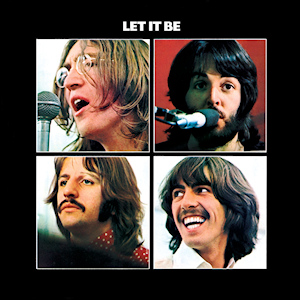

Let it be (May 1970)

‘Let it be’ or, in other words, ‘stop; give it a rest – leave it alone, now’. It’s strange to think that in April of 1970, The Beatles existed and then, shortly after the release of this record, they didn’t. The Beatles were no more, they have ceased to be. They were an ex-band.

Unfortunately for them, their constant presence and enormous influence and legacy served to make not only the music, but the key-players immortal. How can it possible that The Beatles are no more? Look – they’re everywhere – how can they not… ‘be’?

The solo / group projects that followed are for another list – but no one – no-one – ever, bought any post-Beatles release from any of them and viewed it purely on its own merits. They were always compared to what had come before – and nothing ever came close.

‘Let it be’ is, therefore, the sign-off. ‘We’re not The Beatles any more, we’re going to be ourselves now. Wish us well’. Fat chance. We, the public – the whole world in fact, are just not going to let that happen. And that, at the moment when they just wanted to get on with their lives and not be a Beatle anymore, must have been a miserable feeling for them all.

‘Let it be’ is the musical journal of a malaise, a decline in the human spirit, a record of how tight, beautiful and heroic friendships formed from 1957, a bond of determination and creative flourish has become a sluggish, extended, bickering pseudo-family who were clearly getting progressively sick of the sight and very presence of each other.

Only 4 of the 12 tracks feature dual vocals. Maybe not an issue, but difficult not to see that in the context of the imminent split. Side one’s ‘Across The Universe’ stands out – even if the lyrics do struggle a little under a post-millennial / post-hippie bullshit-lens. With the title track, we have an example of another Beatles track adopted by the primary schools and youth clubs. An anthem to peace, calm and unity – which is in fact somewhat trite, repetitive and bland. There. I said it.

Side Two has McCartney’s ‘The Long and Winding Road’ which has endured as a decent love song. Compare this to ‘Across The Universe’ and it’s clear how the two writers were really living in entirely different world in terms of imagination, theme and lyrical scope. It all ends with ‘Get Back’. Decent enough way to go out – but so much less exciting than they way they came in.

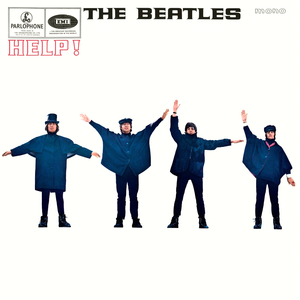

Help! (April 1965)

Five months separate the release of ‘Help!’ and ‘Rubber Soul’. Five months. Twenty weeks, 140 days. That….Is……Ridiculous.

It is not simply the speed of production, it is not just the quality – it is that the difference in tone is so profound that they could have come from different decades and from different bands. If a common indicator of musical creative quality is the ability to re-invent and move on, then the jump from ‘Help!’ to ‘Rubber Soul’ is arguably the best Beatles example.

Whether ‘Help!’ is the soundtrack to a film, or whether the film was inspired by the music is a point for debate. It is tempting to look at the career of the band as a purely artistic exercise, however it would be naive in the extreme to think that a large number of eager company executives were looking at all kinds of ways to exploit the band for every possible penny – and what better way to do it than the cinema?

In filmic terms, consider the difference / contrast between ‘Hard Day’s Night’ and ‘Help’. The former, monochrome, shirts and ties, a one-joke romp through the emerging teen-driven landscape of the sixties. The latter is technicolour – vivid and bright. Surreality combined with an old-fashioned romantic story line – and ultimately…pointless. As an artefact of it’s time, ‘Hard Day’s Night’ is so much more interesting. ‘Help!’ despite tank battles on Salisbury Plain and a trip to The Bahamas has no real legacy and serves to be remembered as little more than a cashing-in exercise by the money-men.

Musically, ‘Help!’ is a way, way better product. The title track combines John and Paul’s vocals perfectly and very much shows them as a creative team pulling together and further on, ‘You’re Gonna Lose That Girl’, ‘You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away’ and the gorgeous ‘Ticket to Ride’ make Side One a breathless success.

Breathless too is the pace. The 14 tracks come in at a total of 33 minutes 44 seconds. This is punk era brevity – and side two, which features the decidedly non-frantic ‘Yesterday’ is actually the high point on a side that is actually pretty forgettable. Somewhat a ‘game of two halves, perhaps; but within the 17 or so minutes of Side One one can find more than enough to satisfy and admire.

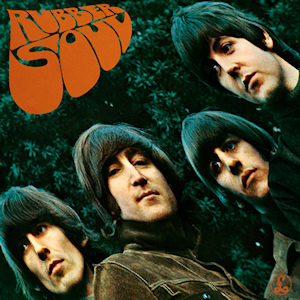

Rubber Soul (December 1965)

This album marks and reflects a career at a crucial turning point and a society at the nexus between youth cultures. The time prior to the release sees a fashion and life-style essentially formed as a sexed-up reflection of their parents’ generation and shortly after, the counter-culture that was set to change the world – not right then – but it was coming. ‘Rubber Soul’ serves as an example of how consistently ahead of the curve The Beatles were. In fact, there is a decent argument to be made here about whether ‘Rubber Soul’ was the most forward-thinking and prescient album of them all.

It’s the drugs. Of course, it’s the drugs. The Beatles had already been introduced to marijuana, supposedly via Bob Dylan but this is the musical equivalent of the band’s first acid trip.

And it was a good one.

The cover shots has the band still sporting mop-tops, but mops that a growing that much longer. The main image is skewed off-centre and the typeset, much imitated (well, copied actually) perfectly reflects the moment.

The influence of LSD was not always for the better on many users but ‘Rubber Soul’ makes it seem innocent, harmless and gentle. The most important thing here is then, right at that instant, The Beatles not only recognised the moment but simultaneously saw the future and showed the rest of the world the way. Everything and everyone else after this was just trying to catch up.

Zeitgeist-defining credentials aside, there’s also the music. ‘Drive My Car’ opens in jaunty fashion; (beep-beep-beep-beep-yeah reminding us of a simpler lyrical time) – but with ‘yes I’m going to be a star’ giving a kind of knowing wink to their rising global influence.

For many, Track Two is the standout. ‘Norwegian Wood’ is the epitome of the idea that this album is the template for UK psychedelia. George Harrison had been studying the sitar with Ravi Shankha and although by Eastern standards, its use here is perhaps simplistic – it is the very fact that hearing this would have been the very first sitar experience for most listeners – certainly in popular music. And you never forget your first time…

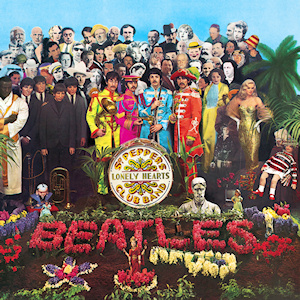

Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (June 1967)

There are many that will dismiss the notion that Sgt Pepper could be anything less than The Beatles’ greatest work – or, indeed, anything less than the greatest album of all time.

Its listing in this placement isn’t some example of contrary iconoclasm looking for an edge. It certainly has it’s merits, it certainly is a work of what could be described as genius, but it has its flaws.

The biggest problem with ‘Sgt Pepper’ is that shared by ‘Yellow Submarine’; psychedelia and that somehow, for a time , it was a case of ‘anything goes’. There was a brief period in the mid 90’s in which saw some awful ‘Britpop’ exponents given mayfly careers (and huge advances) for almost nothing of artistic merit. From that time, came the third Oasis album, wrongly lauded on release to be a masterpiece, but quickly realised to be the result of what happens when far too much cocaine becomes part of the creative process and no-one has the balls to say ‘this is shit’ to the creators.

In a similar way, ‘Swinging’ London’, Groovy Britain and the global embracing of psychedelia at both mainstream and underground levels allowed this album to be made. The difference is between ‘Be Here Now’ and ‘Sgt Pepper’ is that despite both being absolute products of their time and both looking slightly ridiculous in retrospect, the latter does have some properly memorable tunes. ‘Sgt Pepper’ came at the start of an era and defined it, rather than the somewhat sorry overblown and over-indulged fag-end.

And – amongst the diamonds (literally, in the case of ‘Lucy in the Sky…’) there is the dogshit. ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ is the kind of nonsense that primary school kids get taught to sing for end-of-term concerts. ‘Lovely Rita’ and ‘Good Morning, Good Morning’ equally vacuous and eminently disposable.

Credit where it’s due though. EMI insisted that two tracks: ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ and ‘Penny Lane’ would not feature on the album but were instead released on a double A single. This, in itself creates some kind of history and one of the greatest single releases of all time – but including them would have made this album so much stronger with both tunes certainly, somehow, fitting the overall vision.

With ‘A little Help From My Friends’ at one end, ‘She’s Leaving Home’ in the middle and the epic ‘A Day In the Life’ to close – on balance, the wheat outweighs the chaff. However, there is so much here that – if this have been the offering of an unknown band – would have been rejected immediately; but in 1967, who was going to tell Lennon et al that they were wrong?

‘Sgt Pepper’ is, without a doubt, groundbreaking, innovative, inventive and original. But for many of these plaudits, those working at Abbey Road should receive perhaps more credit that history sometime afford them for making the vision a reality. The cover art is, indeed iconic – but it’s Peter Blake’s. Yes, without The Beatles, none of this happens, but without the supporting cast, the main event doesn’t either.

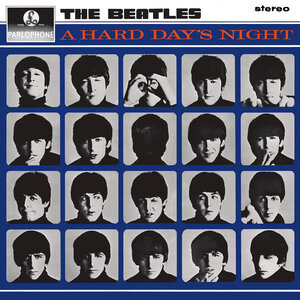

Hard Day’s Night (1964)

The comparison between this and ‘Help’ is discussed above. ‘Help’ is the cash-in movie, and this film was the vehicle that made it all possible.

It’s tempting to focus on the film itself as there is an argument that as a cultural icon, it has a greater significance than the album – but, under scrutiny, how much can most of us reference and recall? The chase at the railway station? Wilfred Brambell and the ‘Bet you’re sorry we won’ conversation? ‘Hard Day’s Night was a first in so many ways – but also musically.

With Side One featuring tracks from the film, the seven tracks come in at 16 minutes 23 seconds. No track breaches 3 minutes and ‘I Should Have known better’ is the longest at 2:43. Saying what needed to be said, so succinctly and so memorably is surely genius. Side Two with one track fewer and 13:47 brings an LP at a shade of half and hour.

So what? 13 tracks – all original. First time….That’s it – that’s the thing. It’s the third album. We’ve grown, we’re in charge and we are a true force to be reckoned with. And we’ve made a movie.

Yes, we’re a pop group – but just look….so much more… and so much yet to come.

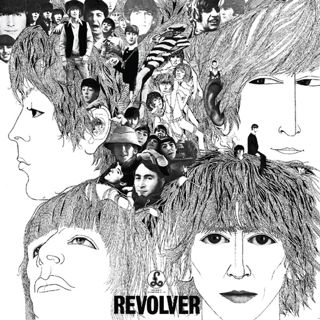

Revolver (August 1966)

Imagine for a moment. It’s August 1966 and you’re 16.

England has just won the World Cup. London is the fashion centre of the world. Harold Wilson’s Labour government promise to take the UK forward into the modern age with ‘the white heat of technology’ and to use a previous leader’s words, the country really has ‘never had it so good’.

Imagine for a moment. The height of Summer. Male or female; it doesn’t matter – you are there the moment ‘Revolver’ is released – and for about £1 12s 6d, it’s yours.1

‘Revolver’ is better than ‘Sgt Pepper’ because of its honesty. It’s a rock album; a collection of tunes, created over a certain time and put together as a package. There’s no artifice, no ‘concept’ – it’s a bunch of tunes in one place take it or leave it. And who could refuse?

The opener, ‘Taxman’, and later ‘Doctor Robert’ takes the band as near to topicality as they ever went (unless ‘The Ballad of John & Yoko’ also counts). Then – ‘Eleanor Rigby’ – the multi-tracked vocals, the strings and lyrics that combined abstract surrealism with real-world reality and with genuine emotional punch.

‘I’m only sleeping’ bridge the LSD gap between the dabbling of ‘Rubber Soul’ to the full-blown habit of the ‘Sgt Pepper’ era. ”Yellow Submarine’ appears with the same incongruity as a giraffe boarding a tube train, but ignoring this hideous anomaly (see primary school comment above) the rest of the album is true class.

‘And Your Bird Can Sing’ rocks, properly rocks and has for my money, one of the greatest guitar riffs ever written. ‘For No one’ tugs at the heartstrings and ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ is very much the predecessor of ‘A Day In The Life’ – certainly its equal and arguably its superior. George’s study of Eastern music comes good; ‘Love to You’ has him properly getting his raga on, the sitar sounding more like a sitar should, rather that one being used as a guitar-substitute.

The Klaus Voormann 2 line-drawn cover is intimate and charming (in contrast to the grandiose ambiguity of Sgt Pepper). In ‘Revolver’ one finds an album of a band firing on all cylinders – aware of their art, but maintaining sufficient feet-on-the ground to not let the art-tail start wagging the musical dog.

So – imagine walking home with your newly purchased copy in 1966. What a moment; what a privilege .

William Wordsworth expresses it perfectly:

‘….Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive,

but to be young was very heaven….’

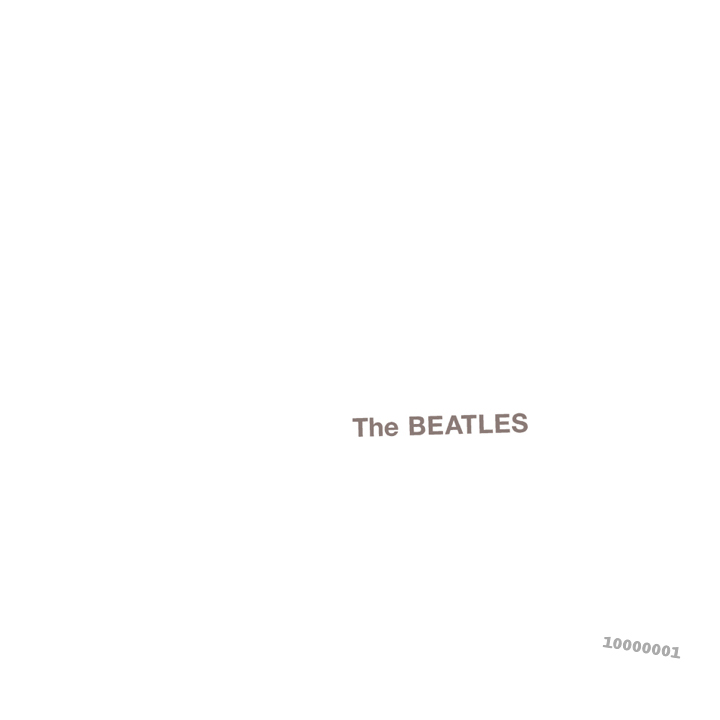

The Beatles (The White Album) (November 1968)

So. ‘The Beatles’, ‘The White Album’ – that which was hijacked in part by Charles Manson; that which seemed to be throwing the public a non-cooperative curve-ball of public withdrawal and wilful obscurity; that which seemed to be laying the foundations for The Plastic Ono Band (but mercifully not Wings) – is the best Beatles album?

Maybe. It’s all subjective. If you’ve bothered to read this far, you’ve probably disagreed with at least half of the above. ‘The Beatles’ may not be everyones’ number one album – but it’s here because – music aside, it’s the most interesting of them all.

‘The Beatles’ is an existentialist crisis for the band. ‘Do we want to do this any more?’ ‘Why are we doing this at all?’ ‘If we don’t do this, what the hell will we do?’ With untold wealth and limitless creative influence it does seem a bit of a stretch to feel sorry for them, but having spent the first three albums doing what they were told, and the last three, doing just whatever they wanted – it must have been a confusing time.

What came out is a behemoth of an album. A double, 30 tracks. Some are great, some are not – just like the rest, but it is the difference that makes – well… the difference.

With a good number of the the songs written while in India – with access to only an acoustic guitar the results often reflect the minimalist nature of their creation. ‘Dear Prudence’ (written about Mia Farrow’s sister who was at the mediation retreat, but refused to come out of her room) is a good example (whisper it – the Siouxsie and The Banshees version is better…) Ob-la-di, ob-la da was written by Mccartney allegedly as a response to Ska – and Lennon called it ‘granny music shit’. Well, it’s not Ska as I understand it – whether it’s shit is up to you.

At this time, The Beatles could, and were doing anything. The newly created ‘Apple Corps’ was busy haemoraging money, John and Yoko were doing the ‘bed-ins’ and Ringo even left – even if it was a very brief departure.

So with all this turmoil and distraction, the disjointed nature of this piece if hardly surprising. There are too many tracks to pick over individually here. Individually, some a laughably experimental – other have endured and others are from a different, easier age. ‘Helter Skelter’ could have been written 10 years earlier and appeared on either of the first two albums and would not have been out of place.

Only the most contrary would seriously argue that The White Album is a better listen than ‘Revolver’. It isn’t. It’s too long by a third and contains the indulged doodlings of millionaires to whom no one would dare suggest were wasting everybody’s time.

Why the album demands so much attention because it represents a time that so much happened in the the life of the band – but remains relatively undocumented. Rumour and rancour exist around the whole Maharishi thing but also Yoko and an uneasy feeling that for the first time, the band were looking like the world, might be moving on at a faster pace than them.

So – finally – why is it at the top? Because, like the depths of our oceans there are unexpected joys, pleasures – and quite possibly monsters waiting to be discovered. It’s and album that asks as many questions as it offers entertainment – and in a world where the obvious seems to be celebrated more and more, a little enquiry and thought can’t be a bad thing.